Utilizzando la matrice di grandi millimetri/metri Atacama ([{” attribute=””>ALMA) in Chile, researchers at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands have for the first time detected dimethyl ether in a planet-forming disc. With nine atoms, this is the largest molecule identified in such a disc to date. It is also a precursor of larger organic molecules that can lead to the emergence of life.

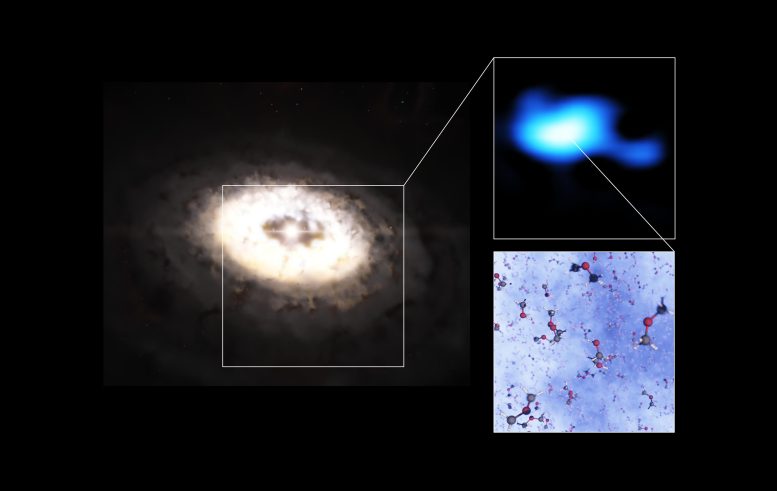

This composite image features an artistic impression of the planet-forming disc around the IRS 48 star, also known as Oph-IRS 48. The disc contains a cashew-nut-shaped region in its southern part, which traps millimeter-sized dust grains that can come together and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids, and potentially even planets. Recent observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) spotted several complex organic molecules in this region, including dimethyl ether, the largest molecule found in a planet-forming disc to date. The emission signaling the presence of this molecule (real observations shown in blue) is clearly stronger in the disc’s dust trap. A model of the molecule is also shown in this composite. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/A. Pohl, van der Marel et al., Brunken et al.

“From these results, we can learn more about the origin of life on our planet and therefore get a better idea of the potential for life in other planetary systems. It is very exciting to see how these findings fit into the bigger picture,” says Nashanty Brunken, a Master’s student at Leiden Observatory, part of Leiden University, and lead author of the study published on March 8, 2022, in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Come finiscono le componenti della vita sui pianeti? La scoperta della molecola più grande mai trovata in un disco di formazione di pianeti fornisce indizi a riguardo. credito:[{” attribute=””>ESO

Dimethyl ether is an organic molecule commonly seen in star-forming clouds, but had never before been found in a planet-forming disc. The researchers also made a tentative detection of methyl formate, a complex molecule similar to dimethyl ether that is also a building block for even larger organic molecules.

“It is really exciting to finally detect these larger molecules in discs. For a while we thought it might not be possible to observe them,” says co-author Alice Booth, also a researcher at Leiden Observatory.

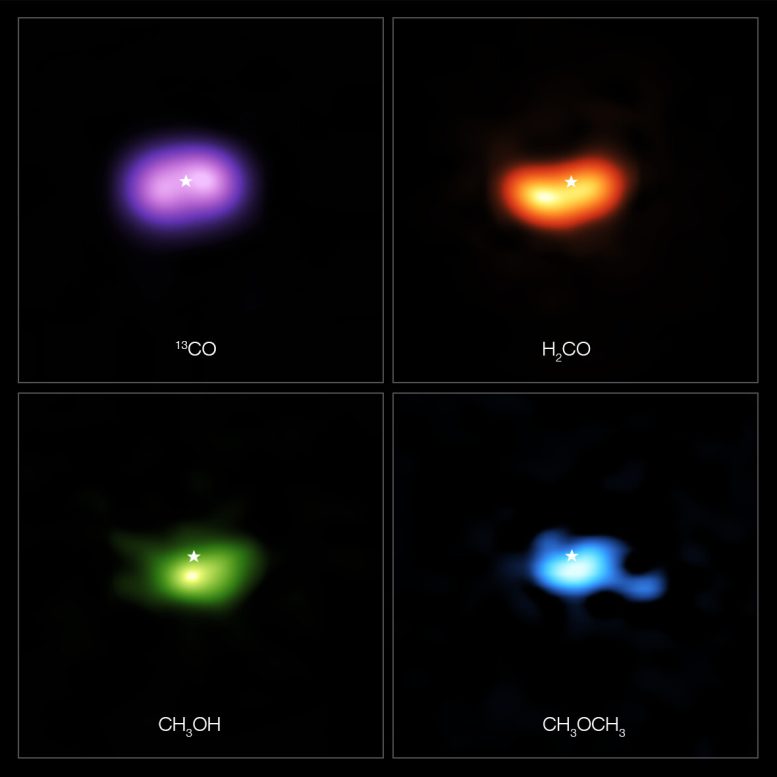

These images from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) show where various gas molecules were found in the disc around the IRS 48 star, also known as Oph-IRS 48. The disc contains a cashew-nut-shaped region in its southern part, which traps millimeter-sized dust grains that can come together and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids and potentially even planets. Recent observations spotted several complex organic molecules in this region, including formaldehyde (H2CO; orange), methanol (CH3OH; green), and dimethyl ether (CH3OCH3; blue), the last being the largest molecule found in a planet-forming disc to date. The emission signaling the presence of these molecules is clearly stronger in the disc’s dust trap, while carbon monoxide gas (CO; purple) is present in the entire gas disc. The location of the central star is marked with a star in all four images. The dust trap is about the same size as the area taken up by the methanol emission, shown on the bottom left. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/A. Pohl, van der Marel et al., Brunken et al.

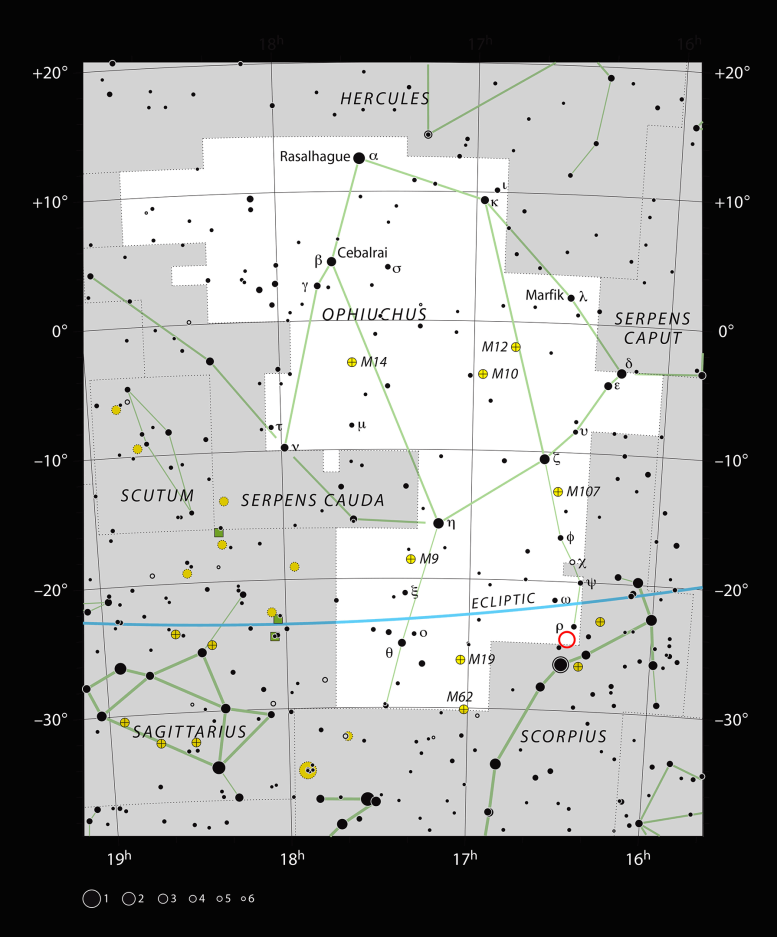

The molecules were found in the planet-forming disc around the young star IRS 48 (also known as Oph-IRS 48) with the help of ALMA, an observatory co-owned by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). IRS 48, located 444 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus, has been the subject of numerous studies because its disc contains an asymmetric, cashew-nut-shaped “dust trap.” This region, which likely formed as a result of a newly born planet or small companion star located between the star and the dust trap, retains large numbers of millimeter-sized dust grains that can come together and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids and potentially even planets.

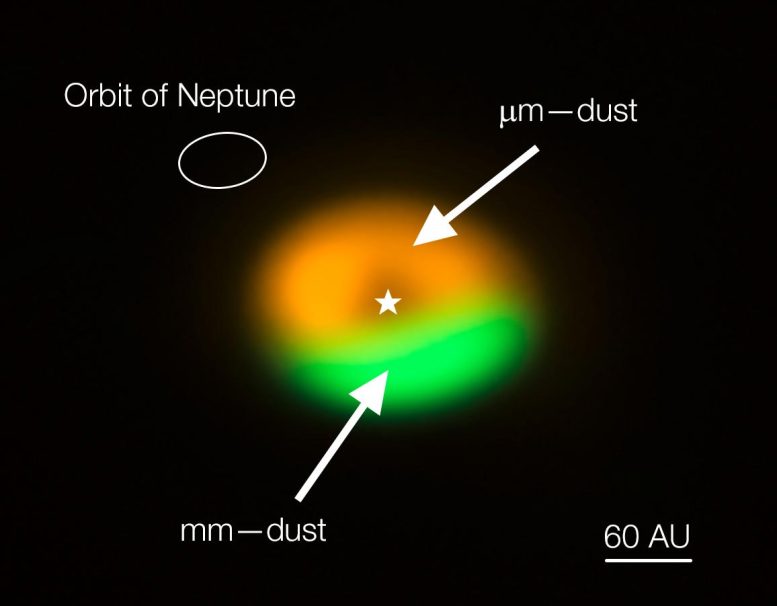

Annotated image from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) showing the dust trap in the disc that surrounds the system Oph-IRS 48. The dust trap provides a safe haven for the tiny dust particles in the disc, allowing them to clump together and grow to sizes that allow them to survive on their own. The green area is the dust trap, where the bigger particles accumulate. The size of the orbit of Neptune is shown in the upper left corner to show the scale. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Nienke van der Marel

Many complex organic molecules, such as dimethyl ether, are thought to arise in star-forming clouds, even before the stars themselves are born. In these cold environments, atoms and simple molecules like carbon monoxide stick to dust grains, forming an ice layer and undergoing chemical reactions, which result in more complex molecules. Researchers recently discovered that the dust trap in the IRS 48 disc is also an ice reservoir, harboring dust grains covered with this ice rich in complex molecules. It was in this region of the disc that ALMA has now spotted signs of the dimethyl ether molecule: as heating from IRS 48 sublimates the ice into gas, the trapped molecules inherited from the cold clouds are freed and become detectable.

Questo video è ingrandito con il sistema Oph-IRS 48, una stella circondata da un disco costituito da un pianeta contenente una trappola di polvere. Questa trappola consente alle particelle di polvere di crescere e moltiplicare i corpi più grandi.

“Ciò che rende tutto questo ancora più eccitante è che ora sappiamo che queste molecole complesse più grandi sono disponibili per nutrire i pianeti che si formano nel disco”, spiega Booth. “Questo non era precedentemente noto perché queste particelle sono nascoste nel ghiaccio nella maggior parte dei sistemi”.

La scoperta del dimetiletere suggerisce che molte altre molecole complesse che si trovano comunemente nelle regioni di formazione stellare potrebbero anche essere in agguato nelle strutture ghiacciate dei dischi di formazione dei pianeti. Queste molecole sono precursori di molecole prebiotiche come[{” attribute=””>amino acids and sugars, which are some of the basic building blocks of life.

This chart shows the large constellation of Ophiuchus (The Serpent Bearer). Most of the stars that can be seen in a dark sky with the unaided eye are marked. The location of the system Oph-IRS 48 is indicated with a red circle. Credit: ESO, IAU and Sky & Telescope

By studying their formation and evolution, researchers can therefore gain a better understanding of how prebiotic molecules end up on planets, including our own. “We are incredibly pleased that we can now start to follow the entire journey of these complex molecules from the clouds that form stars, to planet-forming discs, and to comets. Hopefully, with more observations we can get a step closer to understanding the origin of prebiotic molecules in our own Solar System,” says Nienke van der Marel, a Leiden Observatory researcher who also participated in the study.

Questo video è ingrandito con il sistema Oph-IRS 48, una stella circondata da un disco costituito da un pianeta contenente una trappola di polvere. Questa trappola consente alle particelle di polvere di crescere e moltiplicare i corpi più grandi.

Studi futuri dell’IRS 48 con l’Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) dell’ESO, attualmente in costruzione in Cile e programmato per iniziare le operazioni entro questo decennio, consentiranno al team di studiare la chimica delle regioni interne del disco, dove possono formarsi pianeti come la Terra .

Riferimento: “A major asimmetrico ice trap in a planetary-forming disk: III. First detection of dimethyl ether” di Nasante JC Bronkin, Alice S. Booth, Margot Lemker, Bona Nazari, Ninke van der Marel ed Ewen F. Van Dyschoek , 8 marzo 2022, Astronomia e astrofisica.

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202142981

Questa pubblicazione è stata pubblicata in occasione della Giornata internazionale della donna 2022 e include ricerche di sei ricercatrici.

Il team è composto da Nashanty GC Brunken (Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Paesi Bassi [Leiden]), Alice S. Booth (Leida), Margot Lemker (Leida), Boneh Nazari (Leida), Ninke van der Marel (Leida), Ewen F. Van Dyschoek (Osservatorio di Leida, Istituto Max Planck per le missioni estere, Garching, Germania)