Lo studio è stato condotto in cellule isolate, in tessuto canceroso umano e in tumori umani cresciuti nei topi.

Il nuovo composto, chiamato ERX-41, uccide una vasta gamma di tumori difficili da curare.

Nuova molecola creata dal ricercatore a L’Università del Texas a Dallas Uccide una varietà di tumori difficili da curare, incluso il cancro al seno triplo negativo, sfruttando le vulnerabilità delle cellule che in precedenza non erano state prese di mira dai farmaci esistenti.

La ricerca, che è stata condotta utilizzando cellule e tessuti di carcinoma umano isolati e carcinomi umani di topi, è stata recentemente pubblicata in cancro della natura.

Coautore dello studio e professore associato di chimica e biochimica al College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics dell’Università del Texas a Dallas, il dottor Jung-Moo Ahn ha dedicato più di dieci anni della sua carriera allo sviluppo di piccoli progetti. Molecole che prendono di mira le interazioni proteina-proteina nelle cellule. In precedenza ha creato potenziali composti candidati terapeutici per il cancro alla prostata e il cancro al seno resistenti al trattamento utilizzando un metodo chiamato progettazione logica basata sulla struttura.

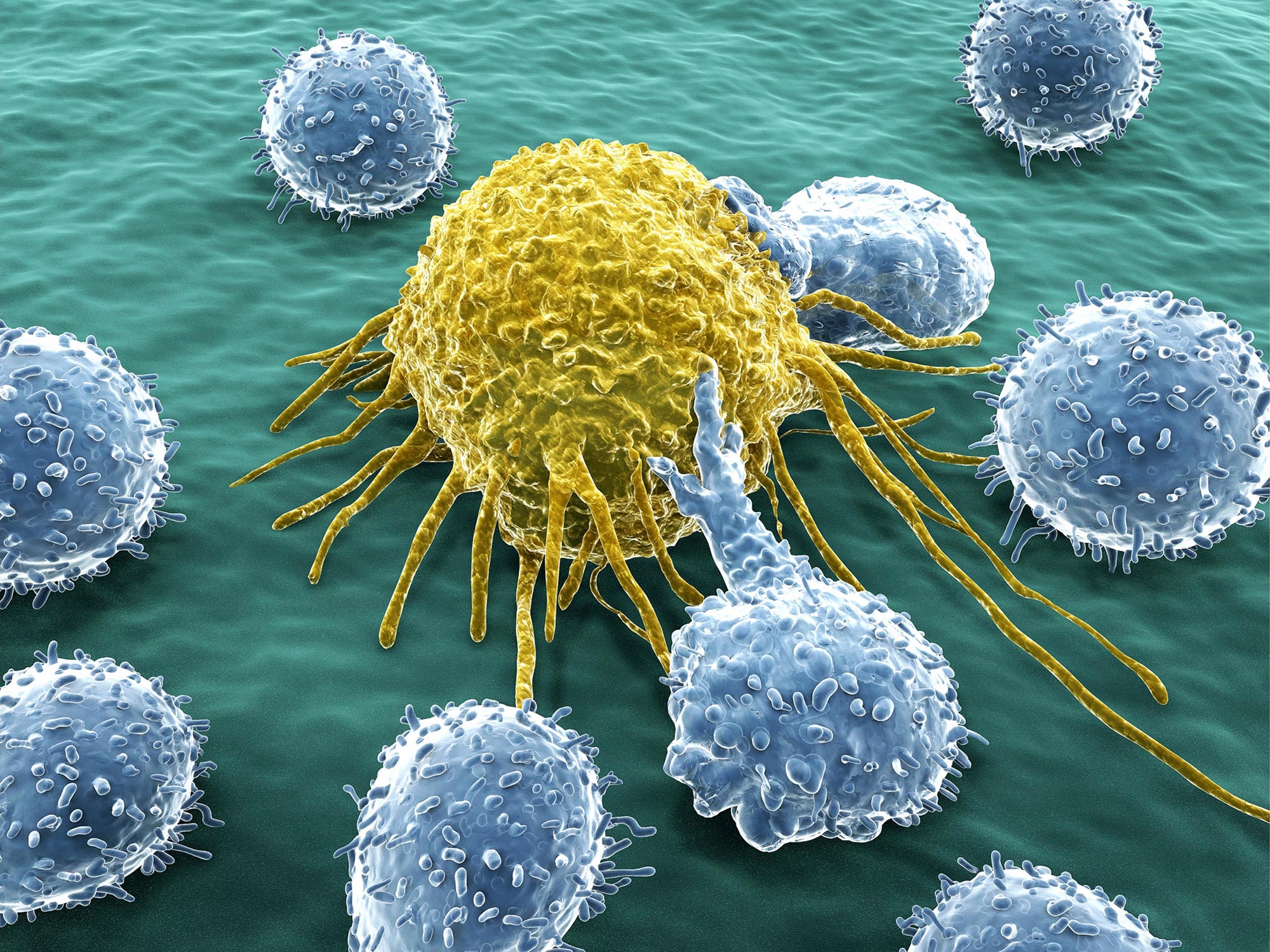

Jung-Mo Ahn, professore associato di chimica e biochimica presso l’Università del Texas a Dallas, ha sintetizzato un nuovo composto chiamato ERX-41 che uccide un’ampia gamma di tumori difficili da curare, incluso il cancro al seno triplo negativo, sfruttando una debolezza nelle cellule che non sono mai state colpite da altri farmaci prima. Credito: Università del Texas a Dallas

Nel lavoro in corso, Ahn e colleghi hanno testato un nuovo composto da lui creato chiamato ERX-41 per i suoi effetti contro le cellule del cancro al seno, sia quelle con i recettori degli estrogeni (ER) che quelle senza. Sebbene siano disponibili trattamenti efficaci per i pazienti con carcinoma mammario ER-positivo, ci sono poche opzioni di trattamento per i pazienti con carcinoma mammario triplo negativo (TNBC), che mancano dell’estrogeno, del progesterone e del recettore 2 del fattore di crescita epidermico umano. Il TNBC generalmente colpisce donne di età inferiore ai 40 anni che hanno risultati inferiori rispetto ad altri tipi di cancro al seno.

“ERX-41 non ha ucciso le cellule sane, ma ha ucciso le cellule tumorali indipendentemente dal fatto che le cellule tumorali avessero recettori per gli estrogeni”, ha detto Ann. “In effetti, ha ucciso le cellule di cancro al seno triplo negativo meglio delle cellule positive dell’ospedale.

“Questo era sconcertante per noi in quel momento. Sapevamo che doveva mirare a qualcosa di diverso dai recettori degli estrogeni nelle cellule TNBC, ma non sapevamo cosa fosse”.

Per indagare sulla molecola ERX-41, Ahn ha lavorato con collaboratori, tra cui i coautori Dr. Ganesh Raj, professore di urologia e farmacologia presso l’Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center presso l’Università del Texas Southwestern Medical Center, così come il Dr. Ratna Vadlamudi, professoressa di ostetricia e ginecologia Donne presso UT Health San Antonio. Il dottor Tae-kyung Lee, un ex ricercatore UTD nel Laboratorio di chimica organica/medica di Ahn, è stato coinvolto nella produzione del composto.

I ricercatori hanno scoperto che ERX-41 si lega a una proteina cellulare chiamata lisosomiale[{” attribute=””>acid lipase A (LIPA). LIPA is found in a cell structure called the endoplasmic reticulum, an organelle that processes and folds proteins.

“For a tumor cell to grow quickly, it has to produce a lot of proteins, and this creates stress on the endoplasmic reticulum,” Ahn said. “Cancer cells significantly overproduce LIPA, much more so than healthy cells. By binding to LIPA, ERX-41 jams the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, which becomes bloated, leading to cell death.”

The research team also tested the compound in healthy mice and observed no adverse effects.

“It took us several years to chase down exactly which protein was being affected by ERX-41. That was the hard part. We chased many dead ends, but we did not give up,” Ahn said.

“Triple-negative breast cancer is particularly insidious — it targets women at younger ages; it’s aggressive, and it’s treatment-resistant. I’m really glad we’ve discovered something that has the potential to make a significant difference for these patients.”

The researchers fed the compound to mice with human forms of cancerous tumors, and the tumors got smaller. The molecule also proved effective at killing cancer cells in human tissue gathered from patients who had their tumors removed.

They also found that ERX-41 is effective against other cancer types with elevated endoplasmic reticulum stress, including hard-to-treat pancreatic and ovarian cancers and glioblastoma, the most aggressive and lethal primary brain cancer.

“As a chemist, I am somewhat isolated from patients, so this success is an opportunity for me to feel like what I do can be useful to society,” Ahn said.

Reference: “Targeting LIPA independent of its lipase activity is a therapeutic strategy in solid tumors via induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress” by Xihui Liu, Suryavathi Viswanadhapalli, Shourya Kumar, Tae-Kyung Lee, Andrew Moore, Shihong Ma, Liping Chen, Michael Hsieh, Mengxing Li, Gangadhara R. Sareddy, Karla Parra, Eliot B. Blatt, Tanner C. Reese, Yuting Zhao, Annabel Chang, Hui Yan, Zhenming Xu, Uday P. Pratap, Zexuan Liu, Carlos M. Roggero, Zhenqiu Tan, Susan T. Weintraub, Yan Peng, Rajeshwar R. Tekmal, Carlos L. Arteaga, Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, Ratna K. Vadlamudi, Jung-Mo Ahn, and Ganesh V. Raj, 2 June 2022, Nature Cancer.

DOI: 10.1038/s43018-022-00389-8

Ahn is a joint holder of patents issued and pending on ERX-41 and related compounds, which have been licensed to the Dallas-based startup EtiraRX, a company co-founded in 2018 by Ahn, Raj, and Vadlamudi. The company recently announced that it plans to begin clinical trials of ERX-41 as early as the first quarter of 2023.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, and The Welch Foundation.